Verdugo Woodlands has a rich history that reaches back to the 1700s, when Jose Maria Verdugo received a land grant of more than 36,000 acres, known as Rancho San Rafael.

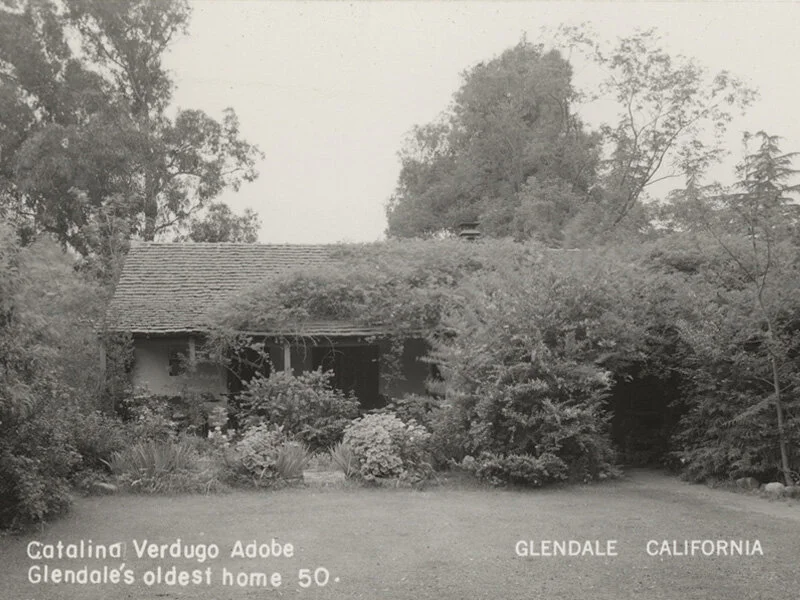

Catalina Verdugo Adobe

Around 1828, Verdugo’s grandson Teodoro built the adobe at 2211 Bonita Avenue and lived there with his aunt Catalina.

In 1847, under a large oak tree at the adobe, the treaty that would end fighting in California during the Mexican American War was negotiated. The “Oak of Peace” was, like the adobe, a historic landmark, until it died in the 1980s. The area is now a popular neighborhood park.

Great Partition of 1871

The Verdugos lost most of their land in the Great Partition of 1871, which divided the property among many claimants. After Teodoro’s death in 1904, the last remnants of the original rancho, including the adobe, were sold. It didn’t take long for developers to see the potential of this verdant environment.

Verdugo Park had been a favorite picnicking destination since at least the 1890s.

Glendale-Eagle Rock Railway

Once the Glendale-Eagle Rock railway line was extended into Verdugo Canyon in 1910, the transportation was in place to lure residents to the area. The “Verdugo Canyon Tract” was marketed as an upscale development of large lots between one-half to three acres in size, close to Glendale.

1912

The area and its precious streams, which provided Glendale with most of its domestic water during its early development, was annexed to the city.

1920s

Lots were bought as investments and changed hands frequently, but they were also built on. Virtually all were resubdivided as the land increased in value.

Developer Frederick Newport was the most prominent developer associated with the Woodlands after 1917. It was he who christened the neighborhood Verdugo Woodlands.

Newport owned property throughout the area and in 1924 developed the east side of Niodrara Drive and Fernbrook Place, the heart of the Niodrara Drive Historic District. Much of the landscape he created along the natural stream, which included ponds, bridges, an ornamental stream bed, and a river rock curb, remains to this day.

Grande Dame of the Woodlands

A few Woodlands houses exist from the teens, including this beautiful American Foursquare/Prairie-style mansion on Wabasso Way from 1912.

Heyday of Revival Architecture

But it was in the 1920s, as Glendale as a whole boomed, that development here took off. This was the heyday of Revival architecture, and the Woodlands still has many original Spanish Colonial and Tudor Revival houses from this era.

The postwar period witnessed widespread construction of the Ranch, which emphasized open floor plans and the integration of indoor and outdoor space. Examples of this popular and quintessentially California architecture abound in our neighborhood.

There are also several examples of Mid-century Modern architecture, a sleek and clean style often featuring post and beam construction and large walls of glass.

The Woodlands’ popularity meant that most development occurred before the 1970s. Our community treasures its history and encourages homeowners to preserve the character and quality of the homes and neighborhood.

Verdugo Views

The following articles were written by Katherine Yamada and published in the Glendale News-Press under the titles “Verdugo Adobe Was Preserved by Developer” 9/8/2001 and “Verdugo Views” 8/4/2001. VWWNA thanks both Katherine Yamada and the Glendale News-Press for their permission to reproduce these articles on this website.

For many years, the old Verdugo adobe at 2211 Bonita Drive was owned by F. P. Newport, developer of the Verdugo Woodlands estates. He purchased it from the heirs of Teodoro Verdugo, who had built the adobe around 1860.

Newport realized the historic value of the place and was careful to preserve it as much as possible. The rose-covered building, the well kept grounds and the famed oak tree, under which the treaty of 1847 was discussed, were magnets for visitors.

Newport invited Mrs. C. R. Philips, whose husband was employed by him for 30 years to live in the house. She remained there for many years, caring for the house and entertaining visitors.

In 1920, a writer who identified himself only as “Old Timer” wrote a glowing account in the Glendale News [sic] of six weeks he had spent at the adobe 11 years earlier. The writer described his arrival at early dusk.

“At a bend in the road almost directly east of the old house, the highway was abandoned and a dash down the hill over the little rustic ridge across the brook brought me to the ranch house.”

By the time the “Old Timer” wrote the account, the rustic bridge was a substantial concrete affair, the shady road was known as Opechee Way and, he says, it led to many handsome modern houses in the new Verdugo Woodlands neighborhood. Soon after his arrival in the historic adobe, the writer was warming himself in front of a roaring fire in the main room.

A woodpile at the rear of the house provided the logs for the fire he enjoyed each evening and for the wood stove in the kitchen. In the corner of the main room was a double bed. The “Old Timer” says he conjured up an image of old Teodoro lying there watching the firelight, then remembered the tale that the old don refused to sleep in the house after an unusually severe earthquake. Instead, Teodoro put his bed out on the veranda and slept there.

A second room in the original adobe was used as the guest chamber. The veranda was furnished with rustic chairs and settees made from gnarled and twisted limbs of trees from the woodlands below the ranch house. With a rug and numerous cushions, the veranda was a comfortable place.

“Setting on the rose-embowered east veranda in the moonlight, listening to the mockingbirds, with the fragrance of the roses filling the air, a day comes to mind when the old don left all this and was borne on the shoulder of sons and friends over the hills to San Gabriel and laid with his forefathers in the old churchyard at San Gabriel Mission. And the dreamer-in-the-moonlight thinks regretfully of bygone days”.

The year was 1847 and John C. Fremont, an officer in the U.S. Army, was on his way toward the pueblo of Los Angeles. The territory of California had just been wrested from Spanish rule by the U.S. Army.

Northern Californians were adapting to the new government peacefully, but in Southern California, a determined band of landowners of Spanish descent were rebelling. They had attacked the garrison in Los Angeles and the U.S. forces had surrendered. Fremont was on his way to help.

After a torturous trip south along the coast, at the height of the rainy season, Fremont arrived at the San Fernando Mission. There he received a visit from Jesus Pico, a relative of General Andres Pico, commander of the rebels.

Jesus told him that U.S. soldiers had just retaken Los Angeles from the rebels and the rebels had retreated to what is now Pasadena. He also carried a message from Pico indicating that he and his men were ready to surrender.

After meeting with Fremont, Jesus Pico left the mission and set out for Los Angeles to meet Pico’s rebel forces. Carroll W. Parcher, in his 1957 “Glendale Community Book”, writes that Jesus met the rebels in the vicinity of an old oak in Verdugo Canyon on January 11, 1847.

Jesus told the rebels of Fremont’s approach and that other American forces were also on their way. He urged the rebels to surrender to Fremont instead of to the other officers, arguing that better terms could be obtained from Fremont. General Pico agreed.

Two days later, the two groups met at Fremont’s new camp in Cahuenga Pass. A treaty was drawn up, stipulating that all native Mexican-Californians should deliver up their arms, return to their homes and assist in keeping the peace. Those wishing to leave could return to Mexico.

This amicable end to the hostilities in Southern California was brought about because of a meeting under the spreading limbs of a tree in Verdugo Canyon. The tree which helped bring about a speedy end to what could have been a long struggle is known as the Oak of Peace and was designated a landmark in 1947.

Sadly, the tree, which was estimated to be 500 years old, succumbed to disease in 1987. Remnants of the original tree can still be seen near the Verdugo Adobe at 2211 Bonita Avenue.

Today, the Oak of Peace is commemorated at Glendale’s train station on West Cerritos. A mosaic-tile image of the tree hangs in the open-air structure where the Metrolink tickets are purchased.

Images courtesy of Special Collections, Glendale Public Library.

And there’s more about Verdugo Woodlands and Glendale’s fascinating history at these websites:

https://waterandpower.org/museum/Early_Views_of_Glendale.html